My local news just broadcast the story I did not want to hear.

The last surviving World War II Medal of Honor recipient in New York State and New England has passed at the age of 94. And I had the honor of calling him my friend and introducing him to some of the Holocaust survivors that he and the 30th Infantry Division helped to save in April 1945.

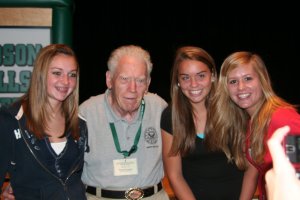

Francis Sherman Currey was humble; he was, as the time of our association from 2008 on, the vice president of the 30th Infantry Division Veterans of World War II. He and Frank Towers, the president, helped to organize and come to our high school in upstate New York for our 2009 gathering of American soldier liberators and the Holocaust survivors they help rescue in 1945. Frank and the others signed autographs for the kids and were treated like rock stars. And in every sense of the word, they were more important than rock stars to these kids.

Frank told me he met Eisenhower, Bradley and Truman after the war. Ike told him that in his opinion, Frank’s actions had single-handedly shortened the war by six weeks or more, by stopping that German advance during the Battle of the Bulge [below]. Later, he was an administrator at the Veterans Administration in Albany and played a role in uncovering corruption. He enjoyed supporting other Medal of Honor recipients— at the White House announcement, our new heroes’ lives are going to change on a dime—but also was content in turning down a White House request for an appearance much later in life, especially when the staffer calling him told him he could not refuse the President. Well, he lived life on his own terms. He also played a large role creating the Medal of Honor Museum aboard the USS Yorktown in South Carolina.

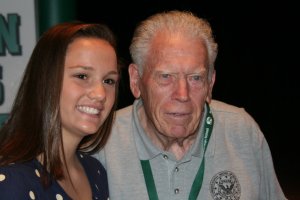

Frank Towers, Frank Currey, Matthew Rozell. September 2009.

Later, I met him in the local airport as he and his wife Wilma were flying out of Albany, New York for our reunions down south with the 30th Infantry Division. It was nice to witness the red-carpet treatment afforded him by our federal authorities as he travelled. I cherish the memory of being honored to sit at the head table with him, medal adorned around his neck, and Towers and their wives at these reunions with soldiers and Holocaust survivors. I especially cherish the late-night hospitality room conversations with the two Franks; he even gave me advice, after we were featured on the ABC World News (you can see him in some nice stills with students near the end of the clip), about the ‘perils’ of the limelight. Once in Nashville I think, we were sitting there alone and were approached by a shy teenage boy and his girlfriend, who wanted to shake his hand, aware of the actions that Frank undertook when he himself was the same age. They turned away, awestruck, and Frank watched them go, with appreciation I think, and maybe even a touch of admiration as well, simply commenting, ‘Youth’.

Both those men are gone now. And I’m struck today that we are losing these guys, these national treasures, our World War II veterans, like a tsunami washing over us. Francis S. Currey was a giant among giants, yet still a simple boy who had had the opportunity to go into the Army, like so many others, to improve his lot in life. He remained true to his roots.

Rest easy, Frank. I’m following with a post about you to help my readers understand more about who you were, and what you did. MR

https://www.today.com/video/wwii-hero-sgt-francis-currey-dies-at-94-71179845879

Nearly seventy-six years ago, it began. Hitler’s last gamble would claim more American lives than any battle in U.S. History. Frank Currey was there, and on a cold winter day in December, saved five men and killed scores of Germans single handedly. Frank was in the 30th Infantry Division, which liberated the Train Near Magdeburg; he came to our school.

The morning of December 16, 1944. A lonely outpost on the Belgian frontier.

In subzero temperatures, the last German counteroffensive of World War II had begun. Nineteen thousand American lives would be lost in the Battle of the Bulge. “Hell came in like a freight train. I heard an explosion and went back to where my friend was. His legs were blown off-he bled to death in my arms.” The average age of the American “replacement” soldier? 19.

Of the sixteen million American men and women who served in WWII, four and a quarter hundred thousand died on the field of conflict. In 2015, on the downward bell curve slope, nearly 500 veterans of World War II quietly slip away every day. The national memory of the war that did more than any other event in the last century to shape the history of the American nation is dying with them. The Germans threw 250,000 well trained troops and tanks against a lightly defended line on the Ardennes frontier in Belgium and Luxembourg, which created a pocket or “bulge” in the Allied offensive line, the objective being to drive to the port of Antwerp to split the American and British advance and force a separate peace with the Western Allies. What ensued was the bloodiest battle in American history. It saddens me that it comes as a shock to many Americans today that the “Battle of the Bulge” didn’t originate as a weight-loss term.

On a personal note, I have had the privilege of interviewing many of the veterans of this battle. In the high school where I teach, I have been inviting veterans to my classroom to share their experiences with our students. As their numbers dwindled, I smartened up, bought a camera, and began to record their stories. And for the past decade, I have been sending kids out into the field to record the stories of World War II before this generation fades altogether. These men and women have helped to spark students’ interest in finding out more about our nation’s past and the role of the individual in shaping it. In our books we have worked to weave the stories of our community’s sacrifices into the fabric of our national history. And that, to me, is what teaching history should be all about. After all, if we allow ourselves to forget about the teenager who bled to death in his buddy’s arms, if we overlook the sacrifices it took to make this nation strong and proud, we may as well forget everything else. I shudder for this country when I see what we have all forgotten, so soon. But if you are taking the time to read this post I suppose I am preaching to the saved.

I will close with the account of a nineteen year old infantryman who in fact survived the battle and the war, and who I was able to introduce to many Hudson Falls students on more than one occasion. Sixty-nine years ago this December, a day began that would forever change his life. Frank is now the only living Medal of Honor recipient from World War II left in New York State and New England.

In the winter of 1944, nineteen year old Private First Class Currey’s infantry squad was fighting the Germans in the Belgian town of Malmédy to help contain the German counteroffensive in the Battle of the Bulge. Before dawn on December 21, Currey’s unit was defending a strong point when a sudden German armored advance overran American antitank guns and caused a general withdrawal. Currey and five other soldiers—the oldest was twenty-one—were cut off and surrounded by several German tanks and a large number of infantrymen. They began a daylong effort to survive.

Francis Currey MOH and Ned Rozell March 2010-Ned is friends with the last WWII Medal of Honor recipient in NY and NE, Frances Currey. Yes, the special edition GI Joe he signed for Ned is 19 yr. old Frank!

The six GIs withdrew into an abandoned factory, where they found a bazooka left behind by American troops. Currey knew how to operate one, thanks to his time in Officer Candidate School, but this one had no ammunition. From the window of the factory, he saw that an abandoned half-track across the street contained rockets. Under intense enemy fire, he ran to the half-track, loaded the bazooka, and fired at the nearest tank. By what he would later call a miracle, the rocket hit the exact spot where the turret joined the chassis and disabled the vehicle.

Moving to another position, Currey saw three Germans in the doorway of an enemy-held house and shot all of them with his Browning Automatic Rifle. He then picked up the bazooka again and advanced, alone, to within fifty yards of the house. He fired a shot that collapsed one of its walls, scattering the remaining German soldiers inside. From this forward position, he saw five more GIs who had been cut off during the American withdrawal and were now under fire from three nearby German tanks. With antitank grenades he’d collected from the half-track, he forced the crews to abandon the tanks. Next, finding a machine gun whose crew had been killed, he opened fire on the retreating Germans, allowing the five trapped Americans to escape.

Deprived of tanks and with heavy infantry casualties, the enemy was forced to withdraw. Through his extensive knowledge of weapons and by his heroic and repeated braving of murderous enemy fire, Currey was greatly responsible for inflicting heavy losses in men and material on the enemy, for rescuing 5 comrades, 2 of whom were wounded, and for stemming an attack which threatened to flank his battalion’s position.

At nightfall, as Currey and his squad, including the two seriously wounded men, tried to find their way back to the American lines, they came across an abandoned Army jeep fitted out with stretcher mounts. They loaded the wounded onto it, and Currey, perched on the jeep’s spare wheel with a Browning automatic rifle in his hand, rode shotgun back to the American lines.

After the war in Europe had officially ended, Major General Leland Hobbs made the presentation on July 27, 1945, at a division parade in France.

source material “Medal of Honor: Portraits of Valor Beyond the Call of Duty by Peter Collier.