I’m at the keyboard this morning thinking of a friend who came into my life only twenty years ago, and who left it a week ago, at the age of 97.

Earl Montgomery Morrow was exactly 50 years older than me, so I can’t say I knew him as well as some, but I knew him on a level enough to realize what his life represented, and what we all lost last Saturday. He called me up, you see, in the summer of 1998. I had been interviewed for the local newspaper in which I explained the project that I had created at the high school where I worked to interview the veterans of World War II, and put the students in touch with their stories.

He said, “I just had to call you and ask—why are you doing this? Why are you interested in our stories?” And that was the start of many visits to the high school where I was teaching.

I gravitated towards our World War II veterans in those years. He was only the second B-17 pilot that I had ever known. Later I would meet other crew members around his dining room table.

Twenty years after our first meeting, in retrospect, he gives me hope for the youth of our nation. He had his own flaws and failures, I am sure—he was flunking out of college when the war came—but he had the determination of a stubborn young man to know what felt wrong, and do what felt right. So against his parents’ wishes—he told his father he wasn’t going back to school—he set off for war at the age of 20. He got into the fledgling Aviation Cadet Program of the U.S. Army Air Corps and proceeded to shoot a cow while on guard duty one night when it would not ‘HALT!’. He got serious then, determined not to wash out, but was told by an instructor on his second day at flight school that he would never make it. Earl asked him why, and the instructor told him he was afraid of the airplane. Earl persuaded the instructor to take him up one more time, to make him or break him. They rolled, looped, dove, flew straight up and then straight back down, touched the wheels down on a big truck going down the highway, and buzzed a farmer working below so low that the man threw a hammer at them and it went over the top of the airplane. Two days later he was soloing, never afraid of an airplane again.

After months in the classroom and on the airfield, he graduated into the pilot’s seat of a multi-engine B-17 bomber. Flying with his new crew before heading overseas, he had to make an emergency landing in a midwestern state during the dead of night. He came in so low that a light came on in a house right below the plane. He circled around, got the plane down, and they waited for parts to be flown in to repair the hydraulics. The incredulous major tasked with flying the parts in asked who the hell landed that crippled plane on that tiny airstrip at night. After that, his crew respected his ability as a pilot. He was all of 22 years old.

For his first mission overseas, he flew in the co-pilot’s seat with a veteran crew with the 457th Bomb Group of the Eighth Air Force flying out of Glatton, 40 miles north of London. All of his 17 combat missions were over Lower Germany. On this first one, he saw these little puffs of black smoke—exploding flak shells. The war becomes personal when people are shooting back at you. He would have his own airplane, but in those 17 missions, he only flew it three times. The rest of the time it was being put back together from battle damage.

He got grounded once. In his own words, he “tore up two airplanes one morning—wrecked them while taking off”, trying to avoid a collision with a command tower. “The night before, someone came in and landed and took a building off its foundation. The colonel said, ‘Next time there is an incident, it’ll be pilot error, one hundred percent’, and sure enough,” he recalled, “it was me!” But he took full responsibility for the mishap, at age 23.

At age 23, I had a history degree and was back in school for teaching. At 23, Earl Morrow was nursing his crippled B-17 across the English Channel when German flak barges opened up and knocked out another engine. He gave the order to throw everything they could out into the sea, praying to make it over the Cliffs of Dover and to an emergency airfield on the coast. Clearing the cliffs, another plane was on the runway, but he brought it in on one engine, a true ‘wing and a prayer’. His men kissed the ground, and they counted over 100 holes in the fuselage. Earl could not even power the plane off the runway.

They rested for a week, and on the next mission they were served real eggs for breakfast—a sure sign that many of the crews would not be coming back from this target, a heavily defended synthetic oil refinery. German fighter planes swooped in after the bombs were dropped and the group turned to head back to England. Earl gave the order to bail out after mortal 20mm rounds hit the cockpit and the plane was on fire. He crawled back up to the cockpit when he realized that the plane might go into a dive, and forced the controls to keep the plane climbing. As he jumped, the plane exploded. He lost three of his crewmen and friends that day, Nov. 2, 1944.

On the ground, he was captured with the lead navigator for the mission, Jerry Silverman of Long Island, New York. Years later I can hear Silverman chastising Earl with a chuckle, when Earl refused to hand over his pilot’s wings to his German captors on the ground. Jerry said that the “big dummy could have gotten us both shot”. Earl responded that he felt he had to push back, so the Germans would show them some respect. They relented.

At age 23 at Christmas 1944, Earl and his fellow prisoners of war were trying to survive in the frozen German stalag system. At age 23 at Christmas in 1984, I was trying to figure out how to survive in the classroom, having made it through my student teaching internship. But I would soon hit upon the simple idea, to put kids in touch with the World War II generation, which would go on to create massive ripples in awakening the past. And Earl would be one of my first ‘co-pilots’ in that endeavor, but he had to survive the war first.

In late January, 1945 as the Red Army closed on Germany in the east and the western Allies were hammering at the West Wall, Hitler himself ordered the mass evacuation of Stalag Luft III to prison camps west of Berlin. Over 100,000 Allied airmen and officers were forced to walk in the most brutal winter conditions of the early 20th century for weeks, dying of dysentery, hunger and exposure and at the hands of guards who killed those no longer able to keep up. Earl himself sat down, disoriented, until a fellow prisoner pummeled him to keep moving. And then Earl was called upon to drag his own disoriented bombardier to his feet; when asked to identify Earl, Sam Lisica said, “I know you! You’re the best damn pilot in the world!”

A few months later, liberation came in the form of General Patton’s Third Army. Earl liked to tell the story of how he was not as mobile as the rest of the men, due to a knee injury, as they rushed towards the center compound of the sprawling camp. As the German guards in the towers disappeared and a flying wedge of tanks and the command jeep with the general appeared, Earl ducked around a building and came out just as the general passed and snapped off a salute to him, which was returned by Patton. Then the fabled general was gone.

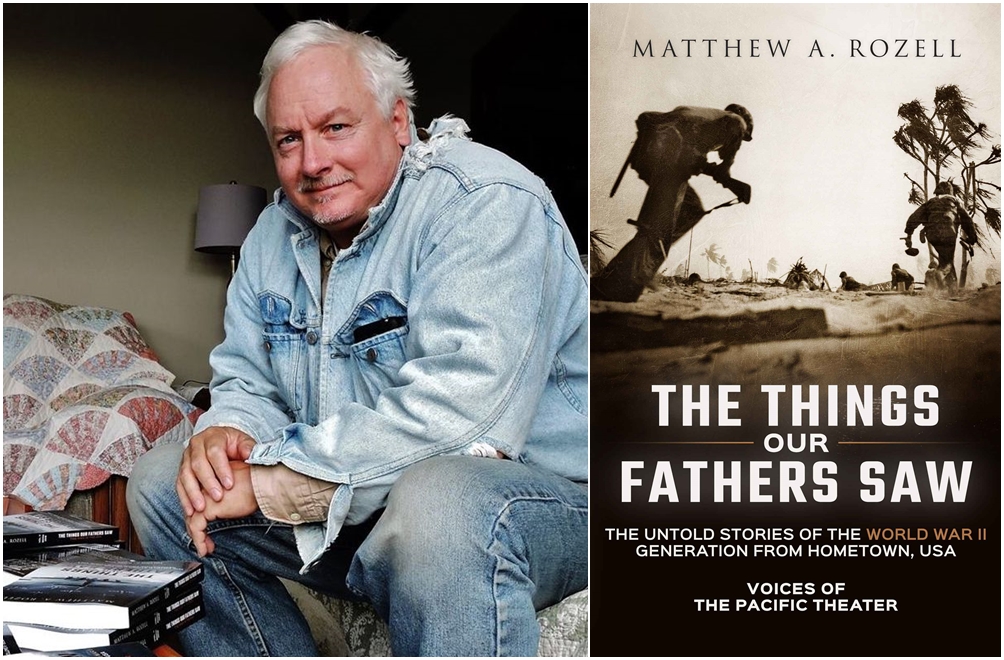

Five decades later, in 1998, I was now an established history teacher. I was sitting around Earl’s dining room table with Sam and Jerry, reunited through the efforts of Earl’s daughter Jessica to celebrate Earl’s 80th birthday here in Hartford, New York, where I now live near that farmhouse where Earl grew up. Earl’s wife Jessie puttered in the background putting up with their banter as I drew the stories out of them, listening to them alternate between seriousness and teasing, laughing together at the funny times, expressing sorrow at the loss of crew members and friends, and wonderment at having survived at all. They basked in each other’s company, and I basked in their presence. Today I thank God that I had the had the presence of mind to record all that, and later I included Earl and his friends in my books.

Sam died in 2006. Jerry died in 2008. Jessie, Earl’s wife, passed in April, 2011. Later, I had Earl back to the high school for Memorial Day ceremonies and veterans’ reunions, where I even got to introduce the granddaughter of General George S. Patton to him. That was a highlight for me, and I hope that gave Earl some comfort as he grieved for Jessie and his friends. “I’m the last one”, he said. But they also gave me and my students hope and inspiration, and I’m sure their examples, as kids themselves thrust into the most cataclysmic events in the history of the world, encourage us all to take a long look at our own efforts to recognize what feels wrong with the world today, and to step up to do what feels right.

I was sitting at a book show on Saturday, staring out the window between talking to my readers and telling his story. I checked my phone, and saw that he had passed. I have interviewed hundreds of veterans and Holocaust survivors, and this is the hardest part of my own legacy to the world. A numbness washed over me, but it was replaced by a burning sensation, an all-knowing goodness that enveloped my heart with warmth as I read the words written by his daughter Jessica:

What a wonderful gift I was given to hold his hand when he drew his last breath. He meant everything in the world to me. Somehow, I am quietly comforted knowing he was met by a woman with her arms folded, stomping her foot, with a big smile on her face. Heaven gained another hero today.

Heroes indeed. And I am reminded of the continuity passed on by Earl and his generation in another quote that surfaced just this morning as I sat down to write, from my past readings, this simple one by the musician Paul Stanley:

I am here because of those who came before. And I will go on because of those who come after.

Life goes on. But it is up to us all to remember such a life as the one lived by my friend Earl Morrow.

***

(Here are the two books I wrote that Earl Morrow appears in. If you wish, you can get them here.)

- Vol. II War in the Air 1

- Vol. III War in the Air 2

Obituary for Earl Montgomery Morrow

Hartford

Earl M. Morrow, 97, of Hartford, passed away on Saturday, December 8, 2018 at the Slate Valley Nursing Home in Granville.

Born on June 27, 1921 in West Pawlet, VT, he was the son of the late Robert and Carolyn E.(Adamson) Morrow.

Raised in Hartford, NY, Earl was valedictorian of Hartford Central School Class of 1939.

Earl served in the USAAC as 1st. Lieutenant Air Craft Commander of the B-17 during WWII. Based in Glatton, England, he completed 17 missions but was shot down over Merseberg Germany on 11/2/44 and taken Prisoner of War. Surviving 3 POW German stalags, he was liberated in May 1945 by General Patton.

Upon returning to the states, he continued his distinguished flying career first transporting Roy Acuff and the cast of the Grand Ole Opry around the country and then to a 30 year career in Chicago with American Airlines, retiring as a DC-10 Captain.

Besides his parents, he was also predeceased by his wife Jessie Morrow who passed away on April 8, 2011 as well as his siblings Robert Rising Morrow Jr., Roberta Morrow Pekins, Everest Mansfield Morrow and Arthur Emerson Morrow.

Left to cherish his memory include his daughter, Jessica Morrow Brand (R. Scott) of Carmel, Ind.; his grandchildren, and the loves of his life, Natalie Morrow, Lilah Claire and Earl Montgomery as well as his other children: Carolyn Morrow Vdorick (Ted), Kenneth Morrow, Barbara Morrow Klein (Tim) and son Drew, and several nieces and nephews.

Friends may call from 10am to 11am on Tuesday, December 18, 2018 at the Hartford Baptist Church, Main St. Hartford.

Funeral Services will be at 11:00am on Tuesday, following the calling hour at the church.

Burial with military honors will be at 1:00pm at the Gerald B.H. Solomon, Saratoga National Cemetery.

Arrangements are in the care of the M.B. Kilmer Funeral Home, 123 Main St. Argyle, NY 12809. For online condolences and to view Mr. Morrow’s Book of Memories, please visit http://www.kilmerfuneralhome.com.