My wife and I went to see the 2025 film Nuremberg yesterday, starring, among others, Russell Crowe as Hermann Goering and Rami Malek as the psychiatrist assigned to him. Overall, while unfamiliar with the story of Lt. Col. Douglas Kelley, I felt the film was generally well done from the aspect of a Holocaust and World War II educator. I felt that, for the most part, the portrayal of chief prosecutor was well done, particularly from the angle of setting precedent for holding war criminals accountable for their individual actions. This was the first time in the history of the world that this had been attempted; leaders of a nation—military commanders, government officials, and propagandists—were held personally responsible for crimes against peace, war crimes, and crimes against humanity, destroying the defense of “I was only following orders.” It created the legal foundation for modern human rights.

The International Military Tribunals debuted in Nuremberg for a reason, which was well brought out in the film. It was the central rallying point for the massive Nazi displays of power in the early days of the Reich—see Leni Riefenstahl’s 1934-35 classic documentary, Triumph of the Will, which I would show to my seniors despite its almost two hour run time— and the sinister 1935 Nuremberg Laws that defined ‘Jewishness’ and codified antisemitism, beginning with stripping German Jews of their civil rights.

What a lot of folks who may be familiar with the Nuremberg trial portrayed here may not actually be aware of is that it was only the first of several trials. Prosecutor Robert H. Jackson set the tone early on.

Documenting the truth of Nazi crimes was the signature achievement. The trials produced an enormous body of evidence—captured documents, films, photographs, eyewitness testimony, and first-hand accounts from perpetrators. The authentic films of the camps upon liberation were included in this movie, and while hard to watch, just like in 1945-46, it showcased that the Holocaust one of the most documented crimes in world history, countering future denial with overwhelming proof.

The trials also set a moral example after a global catastrophe. Rather than executing Nazi leaders summarily—as some Allied leaders wanted—the Allies insisted on a lawful trial. This demonstrated that justice would not be simply vengeance, that the rule of law was stronger than dictatorship, and even the worst crimes deserved legal scrutiny.

To be sure, Hollywood took some liberties. The scenes portraying Jackson as being outwitted by Goering on the stand, and in which the psychiatrist Kelley hands over confidential notes to a gorgeous reporter in an intoxicated state were outright fabrications, to be sure. Others have criticized it for showing the humanity of the chief perpetrators, but I do not have much of a problem with that. For if we hold that they were all monsters, we are just letting humanity off the hook for the next time, as I have written about before, and while I speak for myself, many professionals in Holocaust education circles are in agreement.

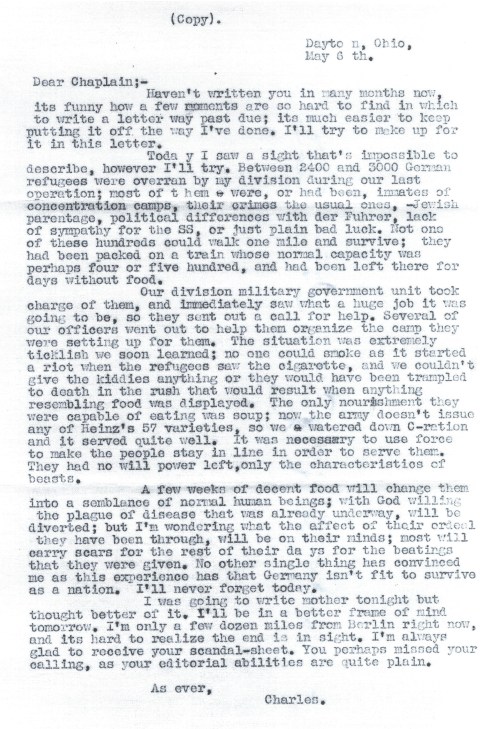

But let’s not forget about the everyday GIs who found themselves at Nuremburg. In Volume 7, Across the Rhine, I introduce at least two of the guards to you, in their own words.

The Courtroom Sentinel

Leo DiPalma was the son of Italian immigrants who grew up in the western part of Massachusetts in the Great Depression. Like many young high schoolers at the time, he was shocked at the news of Pearl Harbor, and ready to serve when his number was called three years later at the age of eighteen. He gained combat experience as an infantryman with the 79th Division, crossing the Rhine in 1945 before being tasked with a new assignment in the 1st Division—standing guard, at the tender age of nineteen, over some of the most notorious war criminals of the 20th century.

I pulled guard duty in the cell block [at Nuremberg]. The cell block was sort of a center, like a star, and all these blocks went off this way [gestures several radial corridors with hand]. Well one of these blocks had the 21 bigwigs, Hermann Goering and Ribbentrop and Hess and all those guys. I was a staff sergeant at the time. I pulled guard on Albert Speer’s cell, and Rudolf Hess. Then after that I was there for a short while, I became sergeant of the guard. I took my regular duties every other day for 24 hours. Luckily, I was asked to go up into the courtroom. I pulled guard with the courtroom guard at one of the visitor doors. After that, I was asked to go up onto the witness stand. That was very interesting, because from where we stood, we weren’t too far from the interpreters. If they were speaking German, and you could pick out [the English translations], you know, so you could know what’s going on, that was very, very interesting. I actually had, at that time, the latter part of the 21 original prisoners, like von Schirach, and Raeder, and Donitz, and Sauckel, right around that area there. I was moving up real fast. I stayed there until July of ’46.

‘Goering and I, We Didn’t get Along’

I had a lot of contact [with these prisoners]. Goering, he was the highest-ranking German soldier there. He expected to be treated like he was a high-ranking officer. The rest of them, believe it or not, they used to bow down to him, let him go first and stuff like that. He and I didn’t get along when I took over sergeant of the guard.

One of my duties was, during a recess, when I opened the door, I stood at parade rest right in the docket where he was right in the corner. I’m sure you’ve seen pictures of it. He would turn to me, and he asked me for some water. ‘Vasser, bitte.’ Okay. I go down to the Lyster bag, which was chlorinated, and I’d get him a little cup of water, and I’d bring it up to him. And he’d take a sip and he’d go, ‘Bah, Americanich.’ You know? He’d hand it back to me. Now there was no way of getting rid of the water; I used to have to walk down to the men’s room on this side to get rid of the water and walk back up.

Mr. DiPalma later recalled that fed up with Goering’s antics, he once met Goering’s demands by replacing the contents of the cup with water from the toilet instead of the tap, which Goering found better than the chlorinated version. ‘I guess I felt it was my little contribution to the war effort,’ he added.

In the meantime, you know, I think he was just doing it on purpose, just getting rid of me. I think one of the things was that he didn’t want to do any talking, didn’t know if maybe I spoke German or stuff like that. I could understand a little bit. But what he didn’t know is, we had some German-speaking GIs right there, and they picked up some stuff on him anyway.

Another time, at night when court was over, one of my duties as the sergeant of the guard was to run the elevator. The elevator was located behind a docket in one of the panels. The elevator carried six people: three prisoners, two guards, and myself, made it [one guard to one prisoner], going up or going down. Well at night, we had to get out of there and run and get our trucks to get back to our billet. Everybody would step back, and there’s big confusion in the docket. [The Germans] let [Goering] go right through, you know. Well, one night, I grabbed ahold of Field Marshal Keitel, he was standing right there. I said, ‘Come on, get in, get in.’ And I dragged him in like that. He was indignant; he was going to let Goering get [in first]. I pulled somebody else in, and somebody else, and I left him, left Goering standing there, you know. I think that was one of the reasons why he would send me for water every day, he was getting back at me.

Another time everybody in the docket was stepping over one another, letting him get out first; they were going to lunch. He didn’t want to cross the hallway where spectators were, he wanted to walk right across—he didn’t want anybody to look at him. So this Captain Gilbert told us, ‘Put him last.’ Okay, so we put him last. Don’t let him stand inside of the doorway. He would wait until everybody went by so he [would have to] walk straight across. Well, I pushed him out there one time, we carried a club, poked him in the back, you know. He turned around and he swung at me, and he hit me on the arm, so I gave him an awful belt in the kidneys. He never said a word to me [after that]. He didn’t like me; I know he didn’t like me. I had a couple confrontations with him, but other than Goering, the rest of them were all pretty good.

Albert Speer, many of them spoke English. I never heard Goering speak English. Albert Speer, he was Hitler’s architect, if you remember correctly. I always felt sorry for him. He was the architect, but he kind of got, I think, using the right word here, sucked into being a Nazi, and he turned out to be a Nazi. Of course, this was all for glory, I guess, for himself. I think Hitler just used him. He was a very calm-speaking individual. Always spoke to the guards. He was quite an artist. He never did me, but some of the other guys that pulled guard on some of these cell blocks, on his cell, he used to draw pencil sketches of them, and they were good. Very, very good. Imagine something like that’s worth a buck today. I don’t have that.

Let’s see, Streicher, he was a pain in the neck, complained all the time. Terrible, terrible. Going back just a little bit, when I pulled guard on the cell block, imagine standing there for an hour and watching the guy sleep through a little hole in the door, you know, it’s awful monotonous. The guys used to talk to one another, and the other guys would get to laughing. Some of them [prisoners] didn’t get much sleep at night. You kind of had to keep it down; when I was sergeant of the guard, sometimes you used to hear hollering down there, so I had to go down there and tell the guys to knock it off. Have you ever seen the old German pfennig? It’s their penny. It’s about as big as our half dollar. Well, one of the things they used to do at night, this wing had a terrazzo floor. These guys would roll these pennies down the terrazzo floor, and it sounded like a freight train coming down through there! [Laughs] I’m surprised that a lot of the German prisoners could stay awake in the courtroom the next day.

Another night, I was in the guard office, and I had a cot there, I was laying there. I could hear some screaming. I said, ‘Oh my God!’ I went down there and the guard at Streicher’s door, out of monotony, had taken a piece of paper and folded it, and he had ripped a little man out of it, so that when you opened it up, it was a man with just legs and arms like that and the head. And from off his uniform somewhere, he had tied a piece of string [tied to the neck of the effigy]. You had the light on just outside of the cell, and he’s swinging the thing in front of the light, and it’s [silhouetting] on the wall, a man hanging. [Chuckles] Jeez. I really don’t blame him for trying to get through the hours, standing there.

Let’s see, von Schirach, I pulled guard on the witness stand with him. He was head of the Hitler Youth. One day, there was quite a confrontation between him and Chief Justice Jackson. Of course, we could understand him. And he spoke decent English now, but most of his replies were in German. But through the interpreter, we could hear what was going on. They were arguing back and forth about the duties of the Hitler Youth. Well, they called a recess shortly after that, and he turned to me. I was on his left side. He turned to me, and he said, ‘But the Hitler Youth is nothing more than your Boy Scouts.’

I said, ‘Really?’ He doesn’t realize that I was a frontline soldier.

I said, ‘I fought your Hitler Youth!’ He never said a word [after that]. We found Hitler Youth that could take apart our BAR, our M1s, or any of our equipment. So they weren’t Boy Scouts like he wanted to portray them.

The rest of them were all just no problems, really. No problems. Alfred Jodl, he was a signer of the surrender terms. He didn’t talk to anybody. Him and Keitel, they weren’t Nazis, but they originally were Wehrmacht soldiers, and they were good soldiers. But of course, they turned into Nazis afterwards, you know?

*

I came home in July, yeah, about three months before the trial ended. [I was not present when Goering committed suicide]; I think [he died] the beginning of October, as I recall. Everybody was trying to get their autographs. In fact, I have their autographs. All but Hess. Every time you’d ask Hess for his autograph, he spoke good English, because he spent quite a bit of time in England, he said, ‘after the trials.’

Well, you know what our favorite saying was? ‘You won’t be here after the trials.’

Nuremberg’s message endures:

No one, no matter how powerful, is above the law—and the world will remember.