I went up to my camp alone in the Adirondack mountains last night. Part of me needed to get away from the machinations of daily life, but I think I needed to be there to reflect by myself on a momentous anniversary.

Passover in 2025 has begun, a fitting setting to recall the significance of the eightieth anniversary of the liberation of the Train Near Magdeburg. Passover of course is the commemoration of the exodus of the Jewish people from slavery in ancient Egypt.

By the spring of 1945, the evil that had engulfed the world had led to the destruction of two-thirds of Europe’s Jews. Yet by some miracle, a handful of Jewish families were sent out of Bergen Belsen to walk to railcars headed towards an unknown destination as Passover 1945 drew to a close.

Seven days of shuttling on the tracks later, cramped and suffering, this train transport stopped in a slight ravine in a forest, hiding for cover from Allied planes but also awaiting instructions on how to proceed from German commanders as American forces approached from the west, and the Red Army appeared near the Elbe River a few kilometers away near the ancient German city of Magdeburg, which was not surrendering without a fight.

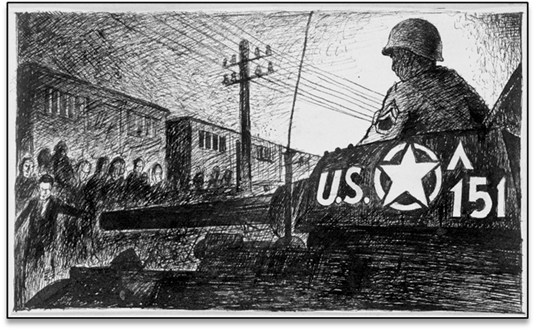

On the morning of the 13th, war weary and grieving solders in two tanks and a command jeep approached the ‘stranded train’, the U.S. soldiers just having learned that morning of the death of their commander in chief, Franklin Delano Roosevelt. They pulled up to the train. Major Clarence Benjamin of the 743 Tank Battalion stood and snapped the now famous photograph of the moment of liberation.

Over half a century later, I began to piece together this story that was forgotten by all except those who lived it—the survivors, and the liberating soldiers themselves. Some of the accounts that I gathered appear in my book, A Train Near Magdeburg (and in the mini-series of which is approaching completion, but no, I can’t tell you where to tune in yet, so stay tuned!). The memory below is from my friend Steve Barry, who passed 13 years ago, but who as a 21-year-old survivor on this day in 1945, remembered this:

There were two tanks. I still get tears in my eyes; that’s what it was. Right now, I have tears in my eyes and I always will when I think about it. That [was the moment that] we knew we were safe.

1945 Ink drawing by Hungarian survivor Ervin Abadi, Credit: USHMM, courtesy of George Bozoki.

We found some matches in those German soldiers’ [rail]cars. We had this tiny little fire going and we were sitting next to it, and I was sitting there with this great big SS overcoat on. One GI walked down the embankment, came over to the fire, sat next to me, took out his pen knife, and he cut off the SS insignia from my coat, and slowly dropped it into the fire. [Gets emotional] If my voice breaks up right now, it always does when I say that, because it’s a moment that just can never be forgotten. I don’t know who the GI was, but it just signaled something to me that maybe I’m safe and maybe the war ended and the Germans, or the Nazis, were defeated. It was an unbelievable symbol to me. And all I can tell you is, it still touches me very deeply, and probably always will.

In this season of liberation, I pause this weekend to reflect on Steven and all the survivors and liberators and their families who have touched my life.

A friend of mine and fellow [non-Jewish] Holocaust educator, Stephen Poynor, posted this morning the words that I will close with here, ones that closely follow the message I have adopted since first sitting down with one of those tank commanders for an interview 24 summers ago, the stories preserved in my book, and in the upcoming film series. Like the soldiers and the survivors who confronted this evil, let us not forget as we continue forward to ‘heal the world’, because that is what good people are called to do.

In a world swollen with division and sorrow, where the weight of injustice falls unevenly and history is too often forgotten or denied, the story of Passover reminds us that liberation is not a moment—it is a journey. Ongoing. Fragile. Worth telling and retelling with trembling hands and hopeful hearts.

We carry these stories not as burdens but as lanterns. We light them for others to see, to feel, to understand. This week, may those lanterns burn a little brighter. May your table be full, your memory deep, and your hope unshakable.

“Hope was keeping me alive.” -17-year-old train survivor Leslie Meisels