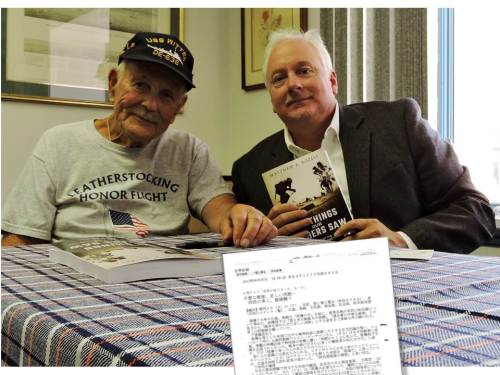

Just finished my 10th book in the Things Our Fathers Saw series, on the CBI theater of the war. I wrote this at the end, thinking about my time with the veterans of World War II.

“It is my earnest hope, and indeed the hope of all mankind, that from this solemn occasion a better world shall emerge out of the blood and carnage of the past—a world founded upon faith and understanding, a world dedicated to the dignity of man and the fulfillment of his most cherished wish for freedom, tolerance, and justice.”

—Remarks By General Douglas MacArthur, Surrender Ceremony Ending The War With Japan And World War II, September 2, 1945

“Can’t we just let go of this war? My father spent four years in, [and] my uncles four years; they NEVER talked about it! Long dead soldiers, long ago war!”

-American commenter on one of the author’s social media posts, highlighting the series, The Things Our Fathers Saw, September 2024

Was it really that long ago?

Seventy-nine years ago last month, Admiral ‘Bull’ Halsey’s flagship USS Missouri was in Tokyo Bay awaiting the arrival of the Japanese delegation with General MacArthur and Admiral Nimitz aboard, positioned near the spot where Commodore Matthew C. Perry had anchored his ‘Black Ships’ on his first visit to Japan in 1853. On display aboard the battleship that morning was the flag that flew on December 7, 1941, over Hickam Field at Pearl Harbor, and the 31-starred Old Glory standard of Perry’s flagship from nearly a century before, now accompanied by hundreds of American warships. The Japanese delegation was escorted promptly aboard at 9:00 a.m., and at MacArthur’s invitation, signed the terms of surrender. As if on cue, four hundred gleaming B-29 bombers roared slowly by in the skies overhead, escorted by fifteen hundred fighters.[i]

National Archives. Public domain.

In the United States and Europe, it was six years to the day that the bloodiest conflict in human history had begun; after those six years of savage fighting, the devastation was unprecedented and incalculable. Between sixty and eighty-five million people—the exact figure will never be known—would be dead. Overseas, the victors would be forced to deal with rubble-choked cities and tens of millions of people on the move, their every step dogged with desperation, famine, and moral confusion. American servicemen, battle-hardened but weary, would be forced to deal with the collapse of civilization and brutally confronted with the evidence of industrial-scale genocide. Old empires were torn asunder, new ones were on the ascent. The Chinese Communists were victorious in China before the end of the decade; the British and other colonial powers began shedding their colonies in South Asia and elsewhere. In 1952, American occupation ended, lasting nearly twice as long as the war with America itself.

Now, the ‘American Century’ was well underway. American power and leadership of the free world was unparalleled and unprecedented. The Marshall Plan literally saved Europe. Enemies became allies. Former allies became adversaries. The Atomic Age began. And the United States of America rebuilt, reconstructed, and remodeled Japan. Of course, this ‘American Century’ was not free from hubris, error, and tragic mistakes, but all of this is part of the legacy that shapes us to this day.

In regards to the end of World War II, I can recall, in the early 1980s as a young history teacher in training, observing a veteran teacher describing the end of the war with Japan by making an analogy to his eighth graders:

‘It’s like two brothers who had a fight. The winner picks up the loser, dusts him off, and they go on as brothers and friends.’

Overlooked, perhaps, were the eight million Chinese civilians and millions of others in Asia slaughtered by Japanese troops in their imperial lust for conquest, the Allied prisoners of war brutalized and worked to death or executed in slave labor camps, the Allied seamen shot while foundering in the water at the explicit orders of the Japanese Imperial Navy, to say nothing of the deceitfulness of Pearl Harbor. I’m sure my twenty minutes observing the teacher in action left out what he hopefully covered in class; he must have known World War II veterans, just as I did. And these are things I suppose you learn later in life, as I did—but only because I wanted to know as much as I could learn. I was born sixteen years after the killing stopped, but ripples of that war have never ended.

If you are a reader of this series, you know how I got our veterans involved once I found my footing in my own classroom. My fascination with World War II began with the comic books of my 1970s pre-teen days, Sgt. Rock and Easy Company bursting off the pages in the bedroom I shared with my younger brothers at 2 Main Street. As a newly minted college grad a decade later, I was drawn to the spectacle of our veterans returning to the beaches of Normandy on the black-and-white TV in my apartment for the fortieth anniversary of D-Day. I was reading the only oral history compilation I was aware of, Studs Terkel’s euphemistically titled 1984 release, The Good War: An Oral History of World War II, over and over. I studied that book, planting the seed for my own debut in the classroom. And in retrospect, I think I reached out to my students asking them if they knew anyone in World War II, yes, as a way to engage them in the lessons at hand, but also to satisfy my own selfish curiosity: just what ‘resources’—really national treasures—did we have in our own backyard, surrounding our high school? I was going to find out. Man, was I going to find out!

Of course they ‘never talked’ about it! Why would they bring ‘The War’ up with their wives, their sons, their daughters? And frankly, most of the civilians they returned home to and surrounded themselves with at work, in the community, and even in their own families, weren’t really all that interested in hearing about it. It was time to get on with life.

But then those guys headed back to the Normandy beachheads, now approaching retirement age, most in their early sixties, if that (about my age right now) …

Somebody was now listening! Somebody gave a damn! And maybe the old soldier could talk about that kid who was shot and lingered on for a while in the far-off jungles of Burma, the country boy far from home who was proud to be a soldier, the eighteen-year-old who wondered now if he was going to die. The combat photographer David Quaid spoke to his interviewers until he was too exhausted to go on. But somebody was interested, and he had things to say—things to get off his chest—before he would no longer be able to say them; like David, a lot of the guys I knew opened up like a pressurized firehose after all those years of silence. It was frankly cathartic, and maybe now they could ‘let go of this war.’

Should we?

I didn’t respond to the commenter in the thread, but another person added,

“I understand, but if there is no conversation, nothing gets shared—nothing gets learned! May your family all rest in peace!”

I know in my heart that opening up to others, even complete strangers, but especially to the young, finally brought our veterans peace.

[i] Dower, John W. Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II. New York, W. W. Norton & Company. 1999. P. 43.