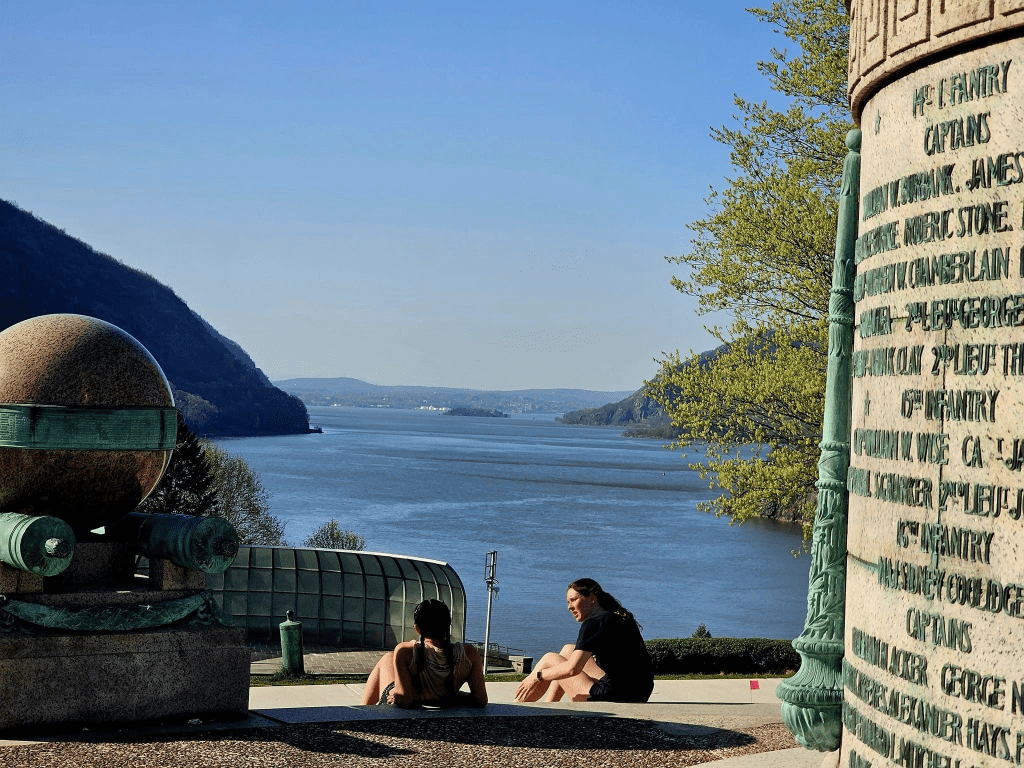

Yesterday I had the great honor of presenting to the senior leadership, faculty, and most importantly, the cadets at the United States Military Academy at West Point, in the scenic Hudson Highlands only a few hours south from my former high school at Hudson Falls.

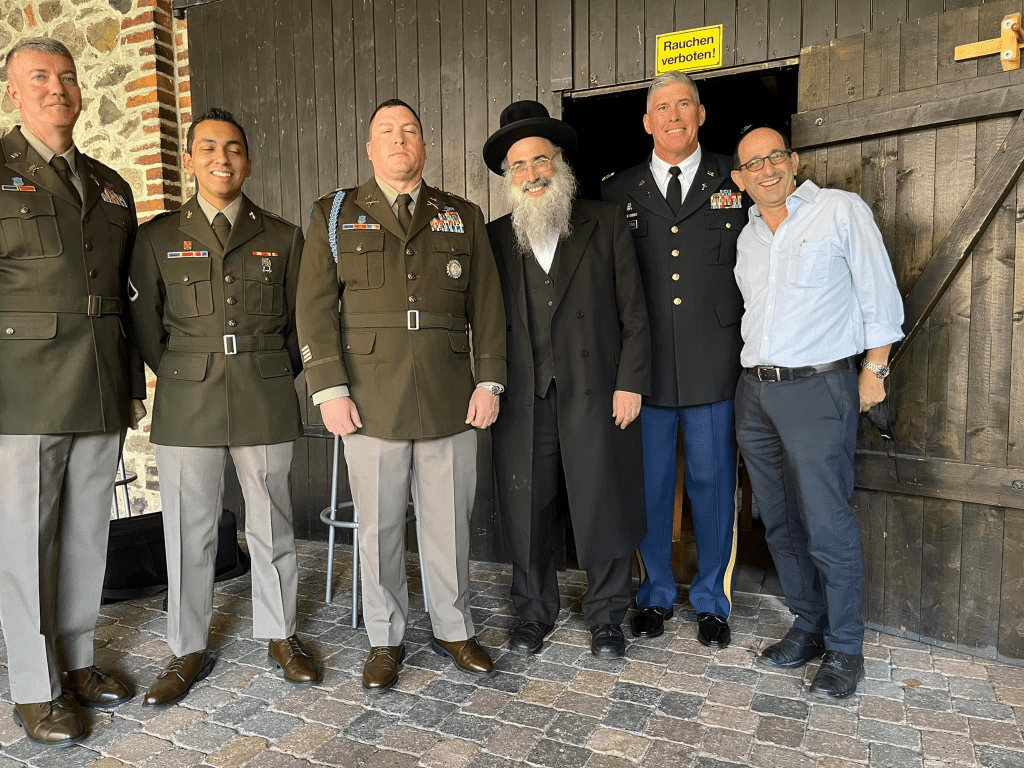

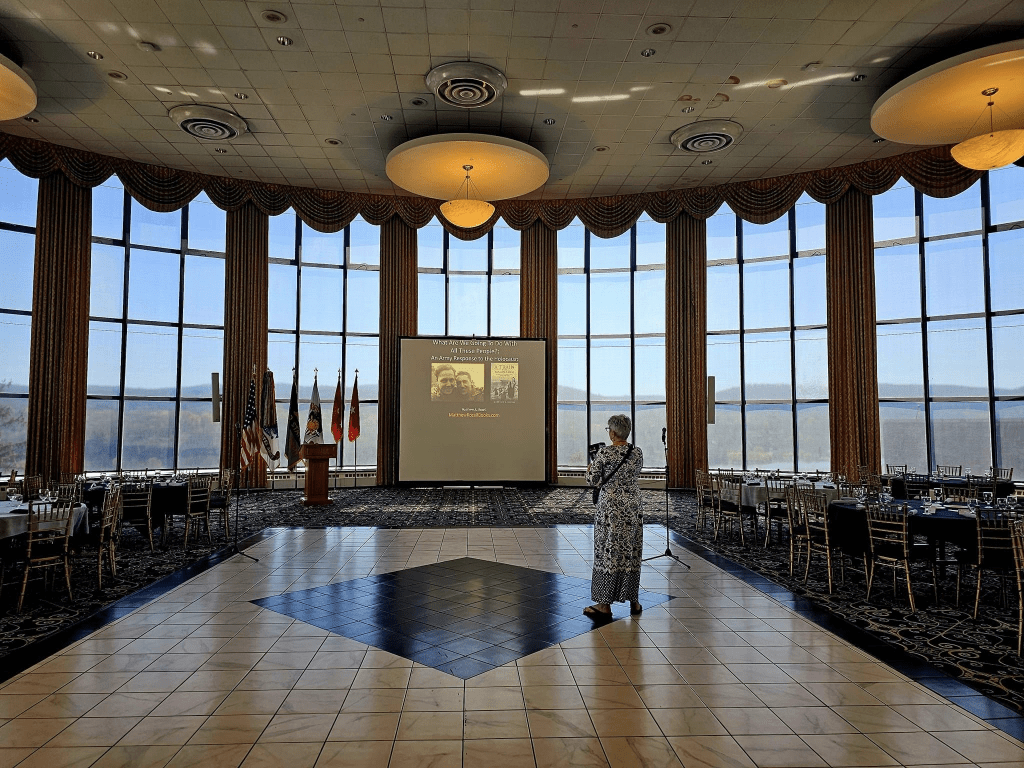

It was a bright and beautiful summer-like day. The master sergeant and lieutenant colonel who were charged with planning and executing the commemoration of Holocaust Remembrance met us at the hotel on the base and we entered the beautiful room overlooking the Hudson where I was to speak to this group over lunch. As it turned out, I was addressing the soldiers at the exact time and date of the liberation of the train 78 years ago. My wife Laura and filmmaker Michael Edwards accompanied me.

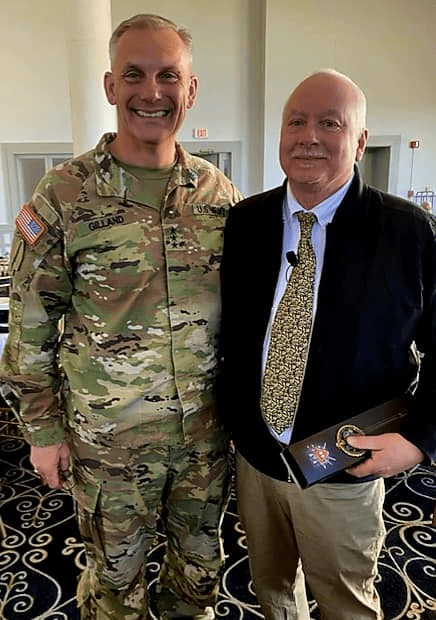

To my surprise and immense gratification (see previous post), the Superintendent of the USMA at West Point, General Steven Gilland, and his wife, and other senior officers, the Commandant, Sergeant Major, were in attendance, seated right next to us. They took the time out of their busy workdays to commemorate and learn more about the the Holocaust; they spend their days preparing to protect and serve. They know that the unthinkable can happen. This is what they do, but this is a story they had not heard before, a message to humanity, of what ordinary soldiers did when thrust into the crisis of witnessing extreme suffering and distress of their fellow human beings.

I told the story, I educated, and I pointed out the ethical and moral choices our GIs made at that time, that day, 78 years ago to the moment of my address. I didn’t preach, I just offered up the story that, indeed, is their legacy. This may be the most important audience, our future young leaders, for the lessons I was presenting.

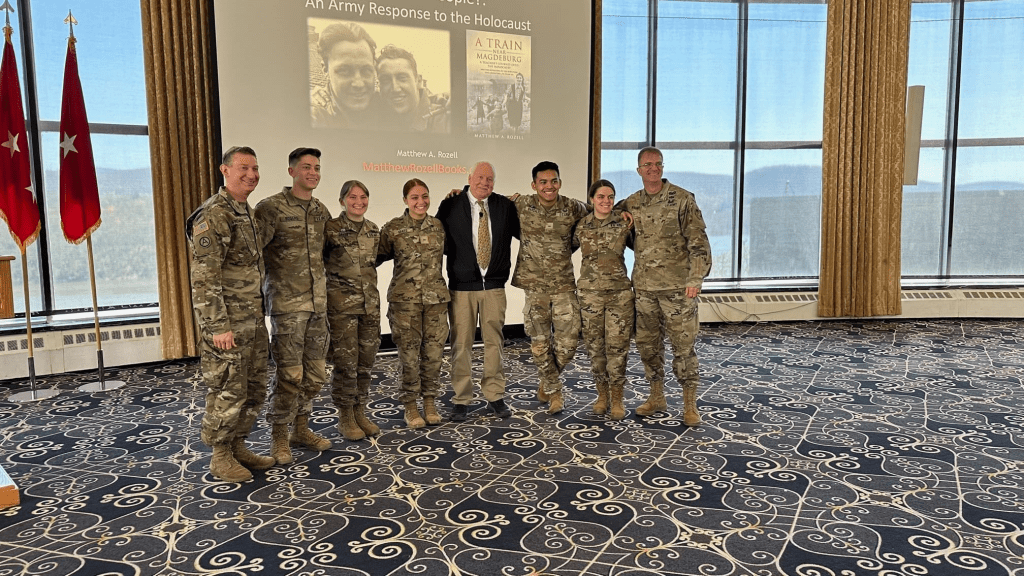

Afterwards, I met some of the cadets, some of whom were eager to speak with me before heading back to class. To a person, my wife and I were impressed with the way that they conducted themselves, in that room and all over the base/campus. We took a late afternoon walk; every cadet jogging by said hello with a smile, and the diversity of the ‘kids’ and staff was impressive. West Point’s diversity credo is “to reflect the racial and ethnic composition of our enlisted force and our country. We believe a diverse student body results in a superior education for our cadets and in phenomenal leaders for our nation’s enlisted soldiers.”

And this is what our soldiers fought for. To paraphrase Dr. Yehuda Bauer, democratic forms of government are in reality new experiments, not perfect, but stand out from all others in their protection of minorities. These young men and women will protect and serve these ideals. What better lesson than the one I was sharing, 78 years to the day?

Later, I walked alone in the West Point cemetery overlooking the river, this same river where further upstream, in my youth, I wandered the banks on summer mornings in pursuit of adventure and wonder. Now, I was surrounded with the resting places of those who served and protected our nation from its earliest days to the present times. And in these seemingly troubled times, division and strife on our doorstep, laments over the state of our youth, today I am comforted by the young men and women I met, the heroes that surrounded me, the natural cadence of respect and goodness manifested everywhere we walked. I hope that when our film is out, more of these young people can become aware of the legacy of what these American soldiers did on a sunny early afternoon 78 years ago. But I feel good. I feel comforted.

I needed this.

Duty, Honor, Country. Those words mean something here. I hope that I helped reinforce those ideals; letting our present and future leaders know just what their GI predecessors did when they became witnesses to the greatest crime in the history of the world.

Off now to Israel to interview more survivors of the Train Near Magdeburg for our upcoming 2024 film.

*************

West Point Hosts Holocaust Author During Days Of Remembrance Observance

WEST POINT, NY, UNITED STATES

04.20.2023

Story by Eric Bartelt

United States Military Academy at West Point

In 1945, it did not yet have a name. American Soldiers heard vague rumors of it, but many dismissed it as propaganda put forth by higher command to get them into the right frame of mind to fight the enemy. But, today, its name is spoken as one of the biggest atrocities and despicable acts in recorded human history.

“The Holocaust. That name is not coined for this most horrific crime in the history of the world until the 1960s,” said Matthew Rozell. “Our GIs know nothing about what they’re about to stumble upon. They were certainly not trained for how to deal with this mass of humanity. Their mission is not to rescue, necessarily, but their mission is to capture and take the city of Magdeburg – their mission is to end the war.”

This is a prelude as part of a riveting speech made during the Days of Remembrance/Holocaust Remembrance Observance, hosted by the U.S. Military Academy’s Equal Opportunity Office, April 13 at the West Point Club. The observance of Days of Remembrance was established by the U.S. Congress as the nation’s annual commemoration of the Holocaust. Public Law 96-388 established the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Council and authorizes the actions of the council. Each year, the President of the United States also issues a Presidential Proclamation for the observance.

The event’s guest speaker, Rozell, is a retired high school History teacher from Hudson Falls, New York, who authored the book, “A Train Near Magdeburg,” and the 10-volume book series called, “The Things Our Fathers Saw,” during which he interviewed many Holocaust survivors.

Through his books, and specifically “A Train Near Magdeburg,” Rozell has helped reunite more than 275 Holocaust survivors with their American Soldier liberators. The Jewish prisoners, mostly women and children, were liberated when they were enroute to a concentration camp and Allied Soldiers intercepted it and set them all free.

Rozell began his teaching career in 1987 after he joined the faculty of his alma mater at Hudson Falls High School and taught World History. Rozell also specialized in teaching the Holocaust, but the narrative he told the audience at the remembrance ceremony is something that, “has been a major part of the second half of my life, and obviously, it brought me here to West Point today to meet you and to tell a story.”

At the beginning of his speech, he jumped right in talking about his book, “A Train Near Magdeburg,” which came out in 2017. However, the photograph on the book’s cover has grown a life of its own within the last month.

“I don’t know if you’ve ever seen this photograph before, but it is one of the most powerful historical photos on the Internet (and social media) now,” Rozell said.

The photo depicts an emotional woman with a young child in the foreground walking up a small hill from railroad cars, which are seen in the background among other people, and it was posted by someone on Twitter a month ago and within two days had 2.3 million views.

“The thing about it is people are very curious about the photograph because it is very dramatic,” Rozell said. “It shows a train full of Jews, in the foreground looks like a mother with a young girl, maybe her child, stumbling up from this railroad car, which is an iconic image of the Holocaust with what railroad cars meant … but what is different about this one is these railroad cars actually brought these people to life.”

Rozell spoke in reference to the line from the tweet, “Allied Soldiers intercepted it and set them all free,” to his audience of mostly USMA cadets and young officers.

“The thing about it is they weren’t just Allied Soldiers, but it was young American Soldiers, about your age right now, who stumbled upon this train and really had no idea of what they were about to encounter,” Rozell said. “They had to make a decision in the field. The mission was to take the city of Magdeburg … but they had to do something with these sick and emaciated people who were going from one concentration camp and being transported to another one.

“This photograph probably wouldn’t have seen the light of day, even today, if I had not sat down with a World War II veteran and got him to tell me his story,” he added.

Rozell prefaced this venture he embarked on from the perspective of a high school History teacher who was responsible for teaching 8,000 years of world history to students in 300 class periods over two years per student. So, he asked the question, “How much time do you have to teach World War II, D-Day or the Holocaust?” The answer was not much.

He then asked a question of his students in the late ‘80s and ‘90s, “How many know a World War II veteran?”

“Every kid in the classroom, both hands went up because it was their grandparents’ generation who fought World War II, their aunts or uncles and, in some cases, even their parents,” Rozell said. “So, I devised a survey to take home with my students … and I got so many surveys back.”

Rozell illustrated one of the surveys on the projection slide to the audience by a man named Joseph N. Leary. The survey from 1998 by Leary, who was 75 years old then, mentioned him being a survivor of the Battle of the Bulge.

However, in this instance, what Rozell remembered most about Leary’s survey paper was his answer on the back of the document to the question, “What words do you have for the younger generation today about your World War II experience?”

“He wrote back, ‘I don’t know how anybody who wasn’t there could make a person understand what it was to survive a nightmare like a World War II,’” Rozell said. “I then took that as a challenge and we began to invite these veterans into the classroom, and my students ate it up.

“They were wrapped in attention listening to these older gentlemen telling their stories because, in many cases, they realized if they didn’t tell their stories, their friends who they lost overseas were going to be forgotten,” he added. “Their names were going to be forgotten and they wanted to get it off their chest. And we heard some pretty incredible stories.”

The 743rd Tank Battalion stumbles upon a rendezvous with destiny

During Rozell’s guest speaking appearance, he showed a clip from a documentary, projected to be called similar to his book, “A Train Near Magdeburg,” that he has been working on with filmmaker, Michael Edwards, for the past eight years and will debut on streaming platforms in 2024.

In a scene that was viewed by the audience, a male Holocaust survivor said, “We were lower than animals. We (did not have) names. We were not (allowed) to be human beings … we were treated like creatures whose destiny (was to) be dead.”

Those are chilling words of what could have been his fate and the fate of the other 2,500 Jews who inhabited the train that was headed to a concentration camp, which Rozell said there were 54,000 documented concentration camps of the Third Reich, Nazi Germany throughout Europe but mostly concentrated in Germany.

“It was worth it (doing the documentary),” Edwards said. “The reason why we did it is to educate people on the Holocaust.”

Fortunately, destiny had different plans for this group of people whose journey started at the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp. To put into perspective about Bergen-Belsen, like other well-known concentration camps in Dachau and Auschwitz-Birkenau, a German historian who keeps and reconstructed records of people who passed through there said 120,000 human beings passed through or died there during the war.

Rozell said the day the British’s 11th Armoured Division entered the gates and liberated the camp on April 15, 1945, “There were 60,000 emaciated people in various states of dying, typhus and starvation – there were mass graves everywhere. Belsen was a horror show.”

Historically, Bergen-Belsen is where Anne Frank, her mother and sister were shipped to in November 1944. Rozell said they died the following spring about three or four weeks before the liberation of the camp.

“The reason there is nothing there today is the British burnt the camp to the ground because of typhus, but today it is a memorial site,” said Rozell, who toured there with other teachers 10 years ago and then again with Edwards last year.

On April 12, 1945, three days before the Bergen-Belsen liberation, top American generals (Gens. Dwight D. Eisenhower, George Patton and Omar Bradley) walked into a concentration camp, and Eisenhower uttered the words, “We are told the American Soldier does not know what he is fighting for. Now, at least he knows what he is fighting against.”

Rozell said on their visit to a subcamp of Buchenwald, there is a photograph, which can be viewed at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington D.C., of the three West Point graduates walking through the camp with a shot of them with railroad tracks behind them and an area where Germans incinerated the bodies with outdoor open fires in the foreground. Each of them ducked behind a shed to throw up, Rozell said.

However, it was the next day on April 13, 1945, where the train liberation story begins, which happened to be 78 years ago to the day of the remembrance observance.

Rozell said at about noon, two American tank commanders with their major in a jeep were the lead company of the 743rd Tank Battalion, attached to the 30th Infantry Division, on their way to fight the final battle for the city of Magdeburg, which would happen two days later. But, as Rozell said, “(They) went to find out what and why these thousands of people were doing milling about a train near the Elbe River.”

“From your studies of history, the Russians, or Soviet Red Army, were approaching from another direction (east) and the Americans were closing in from another direction (southwest) and they stumbled upon this train and the major (Maj. Clarence Benjamin) stopped and took this photograph (of the woman with a child),” Rozell said. “It appears in the After-Action Report, but it was buried in the National Archives until an interview I did with one of the tank commanders who was there that day.”

The interviews, the photograph, the liberators, the survivors and a story of a lifetime

From the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum website, the Holocaust started when Adolf Hitler came into power in 1933. It is defined as the “systematic, bureaucratic, state-sponsored persecution and murder of six million Jews by the Nazi regime and its collaborators.”

Rozell mentioned that about two-thirds of European Jews were murdered, and when he talked about the liberation of Jews, “They just didn’t go and live happily ever after.”

One of the guys who was interviewed for the documentary film was named Frank Towers, who was a first lieutenant who was a liaison between the 743rd Tank Battalion and the 30th Infantry Division. Towers’ job was to get the people out of harm’s way the next morning, which was Saturday, April 14.

“The survivors that I know … they celebrate (April 13) as if it were a birthday,” Rozell said. “The people Michael (Edwards), my film director, and I have been able to talk to, they cried tears of joy when they recalled this story of their rebirth to us.”

However, the photograph, the corresponding story and eventual book and film would have been lost to history until a happenstance meeting with an 80-year-old man named Carrol Walsh during the summer of 2001. Walsh, a retired New York State Supreme Court Justice, was the grandparent of one of Rozell’s students.

As Rozell explains, Walsh rocked back and forth in his rocking chair sharing his story of becoming a proficient tank commander during World War II. He landed in France in July 1944, following D-Day, and participated in 10 months of combat across northern Europe. His tank unit battled in France as it crossed into Aachen in October 1944, the first German city to fall.

Then his unit moved into Belgium and was involved in the German counter punch, the Battle of the Bulge, and he survived that. By March 25, 1945, his unit crossed the Rhine River as the tank company was moving 18 hours a day until April 12, which also was the day President Franklin D. Roosevelt died.

They got word their commander in chief was dead and the war was not over yet, and then they got word they had to go down and check out what was going on with this train.

“As I alluded with all they went through with 10 months of combat and how exhausted they were, he said to Matt, ‘We’re the fugitives of the law of averages, I don’t know how I survived it,’ as he didn’t get a scratch,” Rozell said of Walsh’s recollection.

Conversely, the train itself was never mentioned during the initial two-hour interview he had planned with Walsh. His daughter, Sharon Walsh Salluzzo, [actually Daughter Elizabeth Connolly] happened to say to her dad at the very end, “Did you tell Mr. Rozell about that train?” as he was ready to leave after the two-hour conversation. He said, “No, I didn’t.” So, it was at that point he started talking about that, “beautiful, fateful day 78 years ago today near the Elbe River,” Rozell said.

While Rozell began speaking about this experience with Walsh, he was projecting a picture of Walsh and the other tank commander, George Gross, and Walsh spoke highly of his good friend.

“(Walsh) said, ‘I was only there for an hour, but George Gross saved this train after they liberated it for the next 24 hours,’ and he had a camera,” said Rozell, who mentioned Gross became a professor at San Diego State University and wrote a narrative about the liberation.

“(Walsh and Gross) gave me this information and we started a website at the Hudson Falls High School World War II Living History project,” said Rozell, who stated the information was taken down after he retired in 2017. “But I do have a blog called, ‘Teaching History Matters,’ that documents all this stuff.”

The two tank commanders with their major investigated the train transport that curiously halted on the railroad tracks, deep in the heart of Nazi Germany.

“As they cautiously maneuvered forward in their Sherman tanks affixed with the white star on the side, they were stunned at what they were encountering,” Rozell said.

This train was part of three transports that left Bergen-Belsen at the end of the war in Europe. The first train, Rozell explained, was liberated at Farsleben, which was “our” train liberated by the Americans. The second train made it to the concentration camp at Theresisnstedt right at the end of the war. The third one was liberated by the Russians across the Elbe River.

“The three transports were Jews who had certificates that showed other countries who might have an interest in their well-being,” Rozell said. “But, these people, don’t get me wrong, were being starved to death when they were on this transport and were liberated.”

The school’s website sat there for four years before Rozell received an email from a grandmother in Australia who had been a 7-year-old Dutch girl on the train.

“She said she saw the photographs on the day of her liberation on our website, and she fell out of her chair,” Rozell said.

She contacted Gross in California from Australia and basically started crying when asking if he had anything to do with the liberation of the train near Magdeburg, Germany, and “that’s how they met.”

“So, Lexie (Keston) was the first person who found the photographs on our website,” Rozell said. “In 2007, myself and ‘Red’ Walsh, which was his nickname as he was Irish, met with three other survivors, one from Brooklyn and one from New Jersey – we got lucky and got them all together.

“Then, over the next 10 years, we heard from over 275 other children who were on the train. There were at least 500 kids on this train,” Rozell added. “We had three reunions at the high school, and that was the first one. There were 11 reunions overall on three continents, including Israel. It took me 10 years to write this book, and Michael (Edwards) is working on a film for the book.”

Rozell said he and Edwards were traveling to Israel the next day, April 14, to speak with 13 more children who were on the train.

From Rozell’s perspective, why is it important to listen to these people? What happens when they are no longer here to tell their stories?

“Once we have absorbed the stories that are in the book and the film – listen to the survivors’ testimony and the Soldiers’ testimony,” Rozell said. “You become a witness. You now have to take these lessons and act on your own. It is especially important to talk to young, future leaders like yourselves because this is your moral, ethical (compass), you’re a leader and people look to you. This is what our Soldiers had to do (in World War II).”

During an excerpt of the upcoming film shown to the audience, the group learned that Towers met with 55 survivors while in Israel. They met a man named Luca Furnari, who lives in the Bronx, who was a child who survived the train. They learned Walsh became friends with many of the survivors and wrote a letter to one of them in response to being called a liberator, he said, “No, I’m not a hero, I was just doing what had to be done. Nobody can repay you for what it has taken from you.” And, that letter currently resides at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum.

The audience also learned about Walter Gantz, who was a medic who took care of the Holocaust survivors for weeks afterward.

“There are certain events that will stay with a person throughout their lifetime,” Gantz said. He added “My parents couldn’t understand why I couldn’t sleep at times,” as he fought back the tears of the scars that still haunted him 65 years later.

Walsh’s daughter, Sharon Walsh Salluzzo, also made an appearance in the film excerpt discussing the photos Gross and Benjamin had taken, and that her father kept copies of them in his top dresser drawer from the time of the war until the end of his life.

“I look back on that now and I think, ‘how unusual,’ because everything else about the war was put away,” Walsh Salluzzo said. “He didn’t talk about the war very much, and yet, those pictures were something that must have touched him very deeply.”

Rozell and Edwards went to Farsleben, Germany, last year to the site of the liberation and took photos of the spot where a monument now sits to the 30th Infantry Division, which has the division’s logo and the word “freedom” written in German and Hebrew on the marbled, squared tribute.

At the commemoration of the monument, Holocaust survivors and their families were present with current members of the 30th Infantry Division, which is now the 30th Armored Brigade Combat Team, and German townspeople and their children.

“The German townspeople have really taken on this project, especially the German school kids, and made it their own because they don’t want this history to be forgotten,” Rozell said. “And, believe me, it was that close to being forgotten.”

Rozell said it is a story that continues, and he is going to continue to set up more interviews with survivors, and many are in their 90s now. He is also continuing to write his world history series from the interviews that his students and Rozell collected over the years before he retired from teaching.

“Many of these interviews reside in the New York State Military Museum, which is based in Saratoga Springs,” Rozell said.

And as he closed his speech, he reiterated the main reason he spoke at the remembrance ceremony was to share this story with those in attendance.

“It is to remind and show you, the future and current leaders of the U.S. military, what your heritage is and this little-known story leads to a much wider audience,” Rozell said. “When I talk about meeting second and third generation Holocaust survivors who now know more about their own American liberators – think about meeting the actual person who saved you 78 years ago and that is what these people had the opportunity to do.

“But as the Soldiers would have told you themselves, the message they would want to leave for posterity is ‘What you do matters.’ We had no idea. We didn’t want to be heroes because we’re not heroes, we were thrusted into this situation,” Rozell said from the Soldiers’ perspective. “They had to make these decisions on the spot and because of that, there are tens of thousands of people who are alive today, and the cool thing about it is they got to learn their actions 78 years ago today led to these future generations being born. That is an important fact – it’s about the story of humanity.

“I’m not Jewish. Michael is not Jewish, but this is a story that every person in the world needs to hear, especially you who represents the United States military because this is what you did,” Rozell concluded. “This is your legacy, so thank you.”

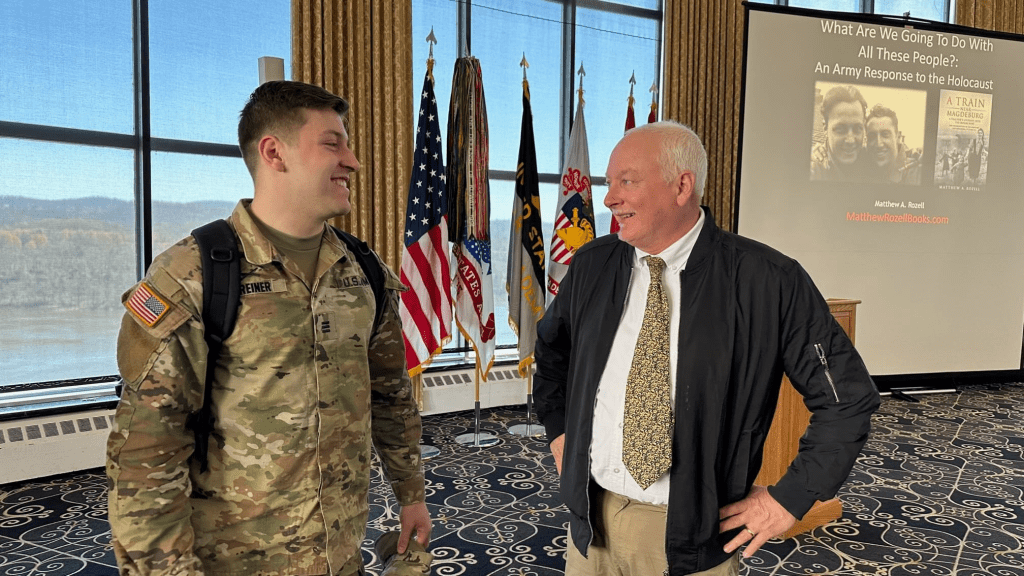

A cadet’s thoughts on the Holocaust and his grandparents surviving World War II

After Rozell, who was named a U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum Teacher Fellow and is a graduate of the International School of Yad Vashem in Jerusalem, Israel’s Holocaust Martyrs, Heroes Remembrance Authority among many accolades, spoke at the Days of Remembrance Observance, he met with a number of Jewish cadets and had a chance to speak to a couple of them. One of those cadets was Class of 2025 Cadet Justin Rogers.

Rogers spent a few minutes discussing with Rozell some of what his grandfather and grandmother went through during World War II to eventually find their way to America.

His grandfather, Salo Katz, who has been deceased since November 2001, was about 15 years old when World War II started.

“Once the Nazi occupation reached Hungary, he joined an underground resistance movement known as the ‘Betar Movement,’ which helped smuggle Jews out of Europe and to present day Israel,” Rogers said. “He was arrested during the war and was put into a concentration camp but was fortunately able to escape amidst an Allied Forces attack of the area, which part of the prison was damaged by artillery and bombs – allowing him to escape during the attack.”

Rogers said once he escaped, he located his father, half-brother and stepmother, and once together, they all immigrated to the United States through Ellis Island in 1951. Once they reached Ellis Island, his grandfather changed his name to Alex Kelton, for fear of anti-semetism against his Jewish background.

As for his grandmother, Erika Falusy, she was born in 1945. However, during the Russian advance through Austria, Rogers’ grandmother, her two older sisters and her mother were displaced by the Russian Army, who had quartered their estate and forced them to live in foxholes just outside their property, surviving on nothing but a mattress laid in a foxhole and whatever food their mother could afford or scavenge.

“Her father was drafted into the war and was never heard from again,” Rogers said. “In 1955, my grandmother and her sisters immigrated to the United States, paid for via bond, to stay with family already living in the United States. Once here, she began taking night classes to learn English while apprenticing as a hair stylist.”

Rogers said years later his grandfather and grandmother met and had two children (Rogers’ mother and uncle) and would eventually settle down in Manchester, New Hampshire.

“My grandmother is still alive and still owns the same house in New Hampshire, but also resides in Naples, Florida, in retirement,” Rogers said.

For Rogers, what did it mean to him to hear Rozell’s speech during the remembrance ceremony?

“I thought Mr. Rozell’s speech during the observance was powerful and made me grateful for people, who aren’t necessarily Jewish, for trying to recreate history for the newer generations and ensure that the stories of Jewish survivors and non-survivors throughout the war are remembered and not lost,” Rogers said. “From this, I was able to take away that although almost 80 years ago, the grueling history of World War II will not be forgotten, and that the lessons learned will help prevent anything like that from happening ever again.”

And what did Rogers believe that not only himself, but his fellow cadets learned about the Holocaust at the observance?

“I think it is important for myself and other cadets to understand and continue to learn about this part of history because it truly serves as a great lesson and example of both the capabilities of humanity to create evil,” Rogers concluded. “And, also to step up to counter evil.”

| PUBLIC DOMAIN | |

| Date Posted: | 04.21.2023 15:06 |

| Story ID: | 443141 |

| Location: | WEST POINT, NY, US |